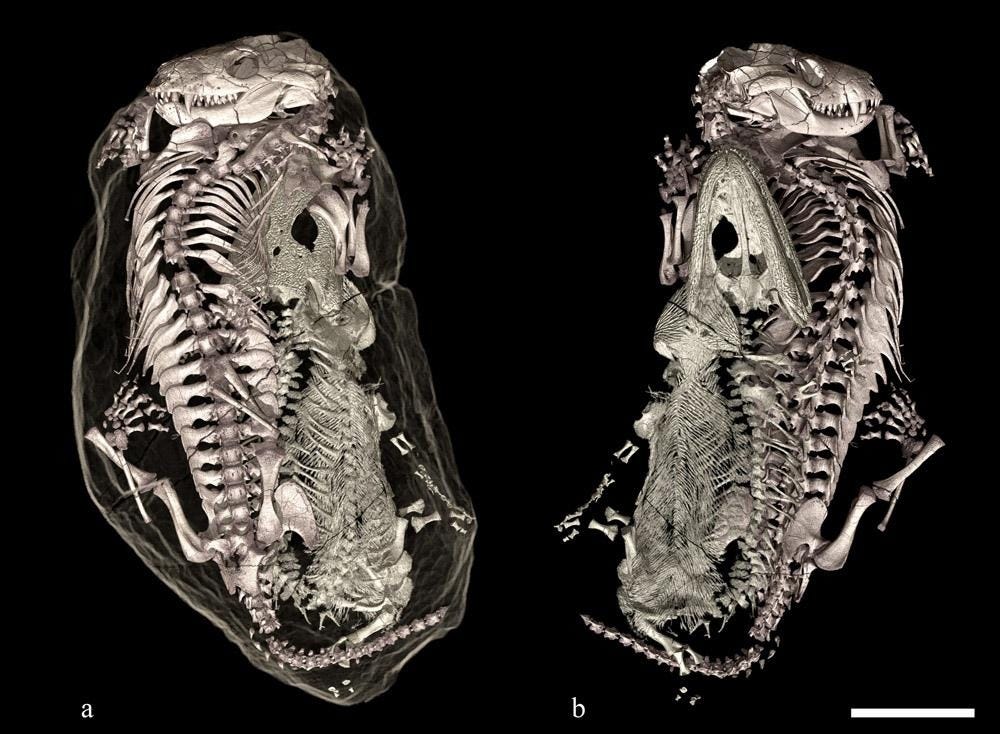

Have you seen that picture? — no, not that one, that’s a diagram — all they found at the beginning was bones and teeth. They think the two of them died in a flood, those unlikely bedfellows. They’ve named it the Triassic Cuddle. A mammal and a reptile curled into each other for shelter, neither of them knowing it would be the last time they touched anything.

I remember asking my mom to scratch my back once, impaired by my inflexibility, my stubbornness, my arms that threatened to split if I asked too much of them. Feeling her nails on my skin, on contours that I myself had never been able to touch. That no one else had ever touched. I curled into my fever and dreamt, dreamt, that I was falling through the layers of the earth, a small, sleeping prehistoric animal that would never awaken again. Perfectly preserved. Then one day, the kick of a football, the prying of curious eyes, and then the laboratories. All they would find was air where they expected bones. And there, between the wings of my shoulders, the golden mould of my mother's fingertips.

My mouth is dry. My eyes are threatening not to be. I am waiting, waiting, waiting, for this to end. The stretch of carpet in front of me seems to stretch out immeasurably, improbably long. I bet if I unfolded my hands from my lap, clicked off the porcelain doll smile stretching my face right now and leaned forward, I could wrap myself around its length.

I like the carpet. I like most things in this room. Sometimes I go home and describe the oak wood lamp to my mother, the one with a face carved into it, and we both get this dreamy look in our eyes. All these things look and smell expensive, though I've never had the temerity - I wish I did - to walk up to her, my knees knocking against her suede covered armchair, eyes level with the top of her head, and ask just how much she paid for them, who she paid. It would be out of order for me to do that, though - usually, it is her doing the asking. She asks. I fight the small animal in my throat threatening to escape, to claw me through, and smile. Eye contact!

I remember writing long ago that the Indian summer was my favourite rite of passage. Another rite of passage for me has been finding out just how diseased I am. For the last two years, I have switched doctors every nine months. We go through this entanglement, this slow, strange, courteous dance of Good mornings and How are yous. You know how I am, bitch, you have the MRI report in your hands.

I could build an ultrasound room from memory. I can do it right now: the walls are dark, soft, almost watery. When I close my eyes I can nearly not tell. When they dance, they do not touch. Stupid thing to read in a book with a stupid premise, some self-gratifying bullshit about Sherlock Holmes’ granddaughter, but it has haunted me for years. When to touch means to destroy, you swallow hard, you don't press the red button. You hover two inches above the air in perpetuity.

Her fingers always feel far too cold for me to not flinch when it starts. They do not hover, possibly because she does not yield much scope for destruction. The gel on my stomach, my jeans slowly lowered to my hips. It used to embarrass me once upon a time, this stop-motion nakedness, but that was me many girls ago. The soundless probe of the scanning device. Once, it rammed into my pelvic bones hard, the winter that I didn't eat and walked around with hollow eyes, and it nearly made me cry, but there is a long gap that bridges nearly and actually. I kept my mouth shut. The doctor speaks to me in Bengali - we both pretend I understand her fully, and that it is mere shyness that prevents me from replying in the same language. I keep keeping my mouth shut. When it's over, I whisper a safe, colonial, sanitary thank you. As soon as the touch began, it ends, and I am alone in the room once again, blinking at the chink of light through the door, reaching for a tissue to wipe myself off, awkwardly shuffling in my shoes till they are firm on my feet.

It is June, and I have never seen such wide streets swaying with trees. My playground was the parking lot, the street dogs my best friends. These trees are massive enough that they have seen years and years of histories. At least a century old. They have lived through independence, through riots and civil wars and elections. They stand defiant, privileged. No one has ever dared to touch them. They live on untouched.

I stood in front of these wide roads this summer, walking to the fifth floor of an apartment building. My gynaecologist's idea - not mine, I swear I had resisted profusely. My dear girl, she said, unrelenting, your face says you need help. Of course, it wasn’t that easy to convince me, but I couldn’t bear to listen to the transatlantic hints of her accent, one which was telling me soul-crushing things about her daughter’s university tuition, and her ability to afford it. And so I dragged my unwilling body to a therapist every week. Five stories up, five stories down, in forty degree Celsius weather. Right next to the old, peeling stairwell was an elevator shaft. Silver, gleaming, monied. Tantalizing with its sheer hints of what could have been. My first day, I tried in vain to press its buttons and summon it, until I realized it could only be accessed with a resident card. So I trudged up, and I trudged down. While I heard and saw people exiting and entering the building, I passed no one else in the stairwell, except domestic helpers. Cooks and maids and cleaning women. Both of us had no choice in the matter, really. Their dinner shifts started when I left, at 5pm. I suppose we were kindred spirits. They were going there to feed, and it was hunger that drove me back again and again.

My father likes telling me that I was born to write. It is a convenient allocation of responsibility in a direction far away from him. He has painted the paintbrush, but left out the hand that holds it, damn him. He likes telling me about meeting my mother at the Times office, both of them free from the clutches of Delhi University's English department, of going on reporting assignments together. Glances from across the newsroom, slow creaking table fans, tidbits of idiosyncrasies from their colleagues which they would carefully commit to memory to pass down to their children: Entire story changes. You are Mr. X! Strange to believe that someone wholeheartedly believes that all this was merely heading towards my future. I wonder if he saw any of this at the time in the summered dusty roads of Daryaganj, shielding his eyes from the heat that threatened to leak in. I wonder if he ever saw me coming at all, a shimmering phantom in the middle of the streets he walked; my hair that sprung out in untameable curls like his, my spite, my bitterness, the dark eyes he sees in the mirror. I raked a personality from the words of the books that he bought me every Wednesday, stopping by the pavement after work ended. Books that would have nearly touched the pavement - sacrilege in Hinduism for the written form to lie on the floor - had it not been for the old plastic tarp between them. Touched by the ground, then the bookseller, and then Papa, who always wiped it with the back of his hand before handing it to me. Reprints of pirated versions that I decadently tore into and finished in mere hours. He would call me to read out each synopsis and wait for my judgement, my selection of the final victim. The books that shaped my shameless hunger, carelessly flirted with it, fanned it, fed it. Was I born to be a writer? What if I told you I wasn't? Entire story changes.

I can screw my eyes shut, you know, but if a hand touched mine, I would still flinch in the dark. Would it make a difference if I had wanted the sensation or not, forgotten how it felt or remained longing for it? Touch cannot be shut away or ignored - it can only be flinched from, turned away from.

About eighty years ago in India, we hadn't yet learned the term 'respectability politics'. It was legal to enforce harsh punishment onto communities so low on the caste rung that they were called untouchables. If an untouchable man began to walk on a road, he had to announce his presence by striking a wooden gong, hearing which the upper castes would run to shield their eyes from his pollution. If you cannot touch someone, can you still unsee them? If you cannot see them, can you still flinch? Later in the social reformist movement, it became even more respectable and even more political to eschew untouchable in favour of dalit, meaning 'broken'. I still wonder sometimes - I don’t want to know the answer - how on earth do you shatter someone without ever touching them?

(Mahatma Gandhi, Freudian father of the nation, refused to say the word untouchable, instead calling them bahujan, children of God.)

(We can assume God had indeed flinched.)

And it irritates me in a way I cannot still describe - I will not say that it makes me flinch - every time I hear the joke about writing being in my blood. I imagine myself sitting subservient and cross-legged in the royal court, taking notes and writing poetry like my father says his ancestors did. Does he know that I listen for any mentions of literature in all my conversations, ears upturned like a mongrel at the door, but that I refuse to even call myself a writer? My ancestors were not men of merit - they were regurgitating as the throne demanded. Two servings of hot bile. Fresh to order. Knowing my father, of course, he would say there is a metaphor here somewhere. But I have closed my eyes by now.

The Indian housemaids I passed by this summer stand at a rather crucial confluence of histories that I don’t think anyone knows what to do with. Eighty years on, we have learned what respectability politics is; we know untouchability is a no-no, even the word itself is a no-no. Interdit, if you cared for French.When I first came across it, I thought it meant between speech. What lies between saying untouchable, and saying no? Making the food is one thing entirely, this bare-armed single-handed wrestle to feed families as large as six or eight or ten people, the naked, ungloved fingers in the roti dough, stirring the curries, serving the rice. All while children who have never been deprived whine about how long it’s taking, how they are starving. Getting rid of desire is one thing, but they still flinch at anything beyond a touch. Nearly every single household requires them to take their thin rubber slippers off at the door, drink their thin tea from separate cups and saucers, not ask for more than the thin band of banknotes they get every month.

Thinness is in; you heard it here. We are no longer dealing with matters of hunger.

The best, most engrossing and most profound essay ive read on substack so far.