My usual visits to the HKU infirmary followed this trajectory: trudging from my student dorm to campus, waiting 15 minutes to be seen by a doctor, feeling the abject shame of having to ask for a medical certificate, and then not leaving bed for hours as soon as I got back.

Not this particular day. I hurried, got seen, got told to rest in bed, and hurried back. An hour later, I was in the outfit I had planned for over a week – three-inch high heels, my birthday pearls, the handbag my mother and sister had bought for me while I murmured assent, and a new dress. I fought my mascara, lined my lips and put makeup on for the first time in months.

"You're really dressed up," said my roommate, who had been watching me with polite discretion. "Are you going somewhere fancy?"

And I grinned, because the telling of it was almost as good as the doing. It felt so grownup, so womanly, so important to tell her I was going to the opening night of Art Central - "VIP pass", I added, because the fact was of importance. She reacted with appropriate surprise. I was twenty and going as a VIP ticket-holder to an art exhibition opening. There was something so glamourous about it in my head.

How it had happened was quite fortuitous - a good friend had received the tickets as part of her internship, but didn't have the time to go that night because of scheduling conflicts. She had generously offered it to me and another friend in the middle of our modern social theory lecture.

And so I traipsed to meet Selina at the Central MTR station, bravely - and foolishly - walking in my heels the whole time. It was almost agonizing (I had forgotten that I can't wear heels unless I'm at least a little drunk, but I opted not to risk mixing with alcohol with the cough syrup I had been gulping all day. As much as I like superlatives, I didn't want to become Art Central's very first fainting visitor). I was carrying more comfortable sandals to change into after we left. It took us more than twenty minutes to find the entrance, by which time I'd already decided to change into my sandals and not care about what I'd be thought about for not wearing heels.

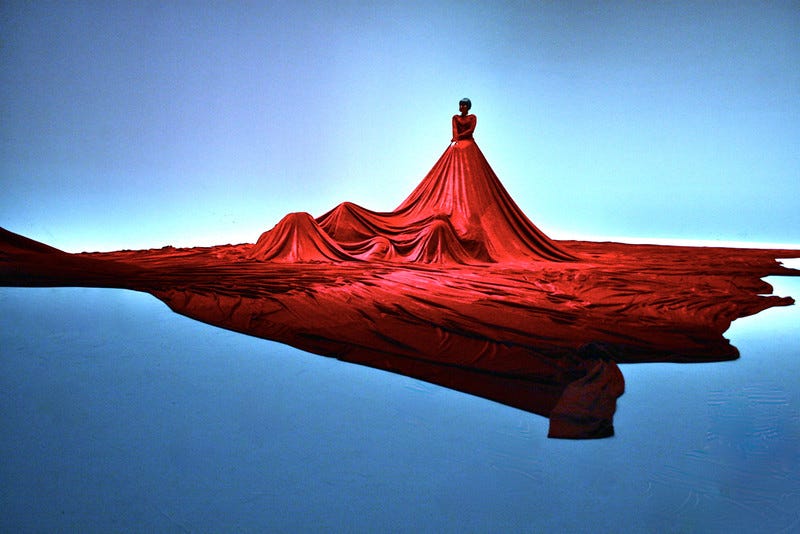

I had had the impression that it would be glamourous, of course, but I also felt like I needed to prove that I belonged there. I squared up, I got my glasses out, I thought about all the Khan Academy art history videos I'd watched in high school and the one course on media and culture I had taken the semester before. Walking in, I made my way determinedly to the outer walls of the space, ignoring the performance art piece of a woman in a red dress right in front of me. Which people were crawling into. She sat up high above the audience, barely disturbed, while the silhouettes of strangers made their way to the centre of her dress like unhatched spider eggs. I read online that the piece was supposed to blur the boundaries between the public and the private under the liminal space of the woman's skirt. I couldn't help but think of it as a birth reversed.

But I didn't go there first, of course. I made it a point to look at the kitschy mounted artwork first, nodding my head vigorously as the docents did their best to navigate my limited Cantonese in their explanations. I refused to be taken in by what I thought was an anti-intellectual manipulation aimed at children. I was not going to go near the red dress, or certainly not into it. I was going to take my time browsing the art which wasn't the most visually demanding thing into the room, screaming my name to come see it. I had a goddamn VIP pass. I was going to act like it.

We did eventually make our way over to the exhibit, and made our way through to the food and drinks section. As far as I could see, everyone passing through the doors carried an identical glass of champagne like an ID card. We briefly contemplated it – I won’t tell you we didn’t – but headed back for the exhibitions, deciding to stop later for dinner somewhere that was more student-budget-friendly. As we were heading back, we were accosted by two white men in their tailored dinner jackets and pink faces, who had apparently been watching us. One of them questioned us why we didn’t get a glass like everyone else.

"Tell me this," went his vaguely trans-Siberian, almost-definitely Russian accent, with all the masturbatory self-assurance I have only heard from men in their forties: "How can you look at art without drinking?"

How, indeed?

The night before, when I was feverish and waiting for my paracetamol to kick in, the words ‘art’ and ‘central’ kept chasing each other in circles in my mind. Despite my haze, the picture they drew in my head was a very definitive one. It was capital-A Art, that much was clear. It was also the only place to find its central location in authenticity and proliferation. Before I finally blacked out, I wondered again why Hong Kong Island’s hotshot business district alone deserved the epithet of being central.

Pierre Bourdieu, in his rare moments of comprehensibility, talked about the existence of art worlds; worlds which existed separately from the material planes all of us live in. These art worlds were conceived of as insular, elite institutions by the Boston Brahmins – upper-class white Americans – in Boston of the 1850s. ‘Us’ and ‘them’ delineations became increasingly popular in a world which they had created for themselves. But I maintain settlers like inventions – of habitats, culture, and themselves. Paul DiMaggio, sociologist and Sociology professor, explained this phenomenon in an article for Media, Culture and Society: that in order to create new institutions of high culture, the Boston upper classes – ‘cultural capitalists’ – had to undertake three simultaneous processes. These were entrepreneurship of an organized form that they could control, classification between ‘high’ art and popular culture, and framing new etiquettes of appropriation between the audience and the art.

Ding, ding ding - I had given into all three of these. I blindly believed that art was central at Art Central; I had declined an invitation to watch the latest Marvel movie in theaters (“Sorry, can’t, art-exhibition-opening-day-VIP tickets”). But I was still figuring out the framing part. I might have been acting the part of a cultural capitalist, but I did not really have the capital to fully assimilate.

And as it turns out, most of the photographs I took at Art Central were of the people themselves – not the art. As the champagne glasses, the Chanel purses, the Louboutins, and the glitz of Hong Kong’s top 1% walked past my beady-eyed gaze, I was the little matchstick selling girl looking in people’s windows, I was Baudelaire’s seething, gaping flâneur, watching the establishment of high art culture in Hong Kong take place right in front of my eyes.

Another win for Asian exceptionalism!

Most people would agree that fast fashion and overconsumption is at the very core of contemporary pop culture. Trends swim in, have their six seconds of fame, and bow out. They might resurface briefly months later, but they never last. I have fallen prey to cherry-red nails, brat summer and bows myself, but I think they make me a calendar, a summation of the exact dates I was looking them up on Pinterest or Instagram’s explore page.

Interestingly, what I’ve seen consistently in inexpensive fast-fashion stores – I’ll take the example of H&M – is a constant trend of cultural capital appropriation. Year after year, I’ve walked to their summer collection racks and seen the following without fail: Yale University sweatshirts. The Chicago Bears hoodies. T-shirts with several odd phrases in surprisingly good French. Poorly-made baby tees that say Amalfi Coast or Champs-Élysées or the Hamptons. Come on, the Hamptons?

Their selling point is that none of these items cost enough to break the bank, but they still semiotically signify a higher cultural capital position than the owner of the clothes has at present. For 70 Hong Kong dollars or 700 Indian rupees, you can wear the sweatshirt advertising the Hamptons (as if you picked it up off a small but chic tourist boutique) back to your private university, which your parents pay private tuition for. You are aware that the private tuition alone bolsters your local cultural status, but you still might stutter while speaking English or feel intimidated in front of visiting American scholars at your university. But voila! the sweatshirt, an indelible mark of you possessing the cultural capital to not only know but also own the signage of the Hamptons. You are part of a small but select community now – who knows, you might be using ‘summer’ as a verb in the next five years.

Middle-class aspirationalism – the common thread joining lowbrow H&M to highbrow capital-A Art Central. The Boston Brahmins used it to be exclusionary; fast fashion uses it to incorporate a wider audience. I think my experience at Art Central convinced me it was a happy middle – after all, I knew the feet wearing the Louboutins would be taking the MTR back home, just like me. Thank god for the equalizing powers of Hong Kong public transport.